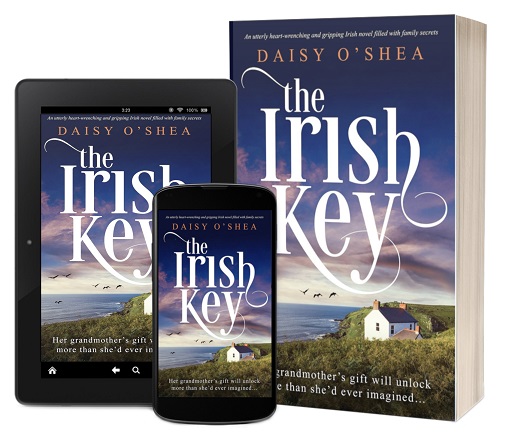

First in a series set in the mythical town of Roone Bay, on the rugged coast of southern Ireland, published in April 2024

BOOK BLURB

Her grandmother’s gift will unlock more than she’d ever imained

THE CONCEPT

The seed of a story can come from anywhere in real life: the hint of a half-heard tale, an odd comment overheard in a shop, a line in a newspaper…

A long time ago I was talking to an older woman – let’s call her Betty – whose husband had died several years back. I was commiserating with Betty, when she admitted that the years following her husband’s death had been the happiest years of her life. I must have looked a little shocked, so she explained that she had married the wrong man. Well, many people marry the wrong person, but back in the early 1950s, despite the rapidly changing social structure, married usually meant for life. She had doubts about her husband before she married him, but he was good with the old blarney, and I guess we all want to believe that the person we’ve fallen for is the right one. As she explained, she had never been popular in school, and had never had a real boyfriend up to this time, and was flattered by the attention. She was just twenty. At the time that was seen as being almost on the shelf, a woman’s raison d’etre, of course, being to find a husband to belong to.

Her doubts grew stronger, but somehow the planned wedding gathered momentum, and in the end, she felt she couldn’t back out as her parents, who had never been wealthy, had laid on the full ‘white wedding’ at vast expense. In post-war England cities were still scarred with bomb sites, goods were hard to come by, and families still had ration cards. So, for a wedding to get cancelled after the women had bought (or more likely made) dresses and hats specifically for the event, it would have been a huge disappointment. In the car on the way to church, Betty’s father said, it’s not too late to turn back. So, he knew she had doubts. She learned, later, that he’d had doubts, too. He didn’t like or trust the man she was going to marry. Her decision to go through with the wedding was basically because the disappointed aunts would have subsequently made her life, and that of her parents, hell for a few months. Instead, she said, my husband did that for fifty years. She worked hard, brought up her children on a pittance, and as soon as the children went to school, she went out to work, but somehow there was never enough money. To the day her husband died, she never knew where the money she earned actually went. She washed her husband’s clothes, cooked, and kept house for him, yet never, in the whole of that time, received so much as a birthday card, or any other token of affection. She said, ruefully, he wanted the comfort provided by a wife, and got one – me.

After he died, she found she had money to spare, but all the things she had wanted to do in her life had passed her by. It would be easy to say, well, if that had been me, I would have left him! But back then divorce wasn’t such a simple affair. A woman had little or no autonomy. She would have had to provide a reason for the application for divorce, and justify this to a panel of men who probably all thought a wife should do as she promised, and obey her husband. He hadn’t hit her, he didn’t gamble, he hadn’t gone with other women, so what could she accuse him of?

This story, sad in itself, provided the ‘seed’ for The Irish Inheritance. I gave my heroine, Grace, an unhappy marriage, but set it a generation later, and gave her the courage to leave. And that is where the story starts… The other notable character in this book is a self-made millionaire. He left Ireland before the famine, and came back to his roots, wealthy, to spend his final years. Despite the familiar stories of emigrants’ dreams often ending in disappointment and tragedy, there were a few exceptions.

The ‘local’ man in my story rebuilt an abandoned and ruined stately home, of which there are many in Ireland. In reality, the cost of such a project would be prohibitive, so they are usually left as romantic ruins, echoes of a past that was not actually very romantic for the cottiers whose labour funded the decadent lifestyle of those privileged owners, who often used them as little more than holiday homes. There is no such place as Roone Manor, but the image in my head is an amalgamation of several magnificent wrecks I’ve visited, including Mount Massey, Macroom, and the even more impressive Mount Leader House, Millstreet. Mount Massey was burned out during the fight for independence in the early 1900s, and the 13,000 acres that supported it were eventually split and sold.

Grace’s current story, in ‘The Irish Key’ is entwined with Noel’s past, the two storyline gradually moving towards an emotional exposé. In the opening, below, I am very conscious of reliving my own first impression of Ireland through Grace’s eyes. When I visited during my late teens, in the 1970s, I was amazed by the sight of children with no shoes begging in Dublin, and donkey carts still on the road. As I left the ferry, I saw a tattered car seemingly trying to climb a lamppost, another car rammed up behind it. I have never forgotten that first impression of the place that was to one day become my home!

Read the first chapter

GRACE

By the time we reach Holyhead, it’s late in the afternoon. Three trains, countless miles we had no need to travel, and Olivia, though I love her with all my heart, is being more difficult than I expected, challenging my already fragile state of mind. She’s bored but not interested in her toys; tired but won’t sleep; hungry but won’t eat the sandwiches I bought – not that I blame her. Sliced bread is a poor substitute for the crusty loaves fresh from the bakery in Cheltenham. I could have brought sandwiches and filled a flask, but had been justifiably concerned about the amount I was carrying.

I’m exhausted, but, thankfully, the eternal are we there yet? ceases as we arrive at the ferry terminal. The water is a swathe of grey, as is the sky in which seagulls are wheeling, screaming their endless cry of hunger. A faint breeze wafts a rejuvenating scent of salt towards us, lifting my flagging spirits.

‘Are we going on that?’ Olivia asks, looking at the ferry with interest.

‘Yes, love. We’re going to Ireland. That’s where Great-Grandma comes from.’

And where Graham will never think of looking.

Graham has never shown much interest in my family’s background, and for the first time, I’m grateful for that. When I was thinking of running, all sorts of unlikely options rattled around in my mind, including Australia – about as far away as we could get. And yet booking a ticket there would have left a trail for him to follow, and Ireland is right on our doorstep, unnoticed, almost invisible. How strange that I never considered it, until Grandma suggested it.

Olivia persists. ‘But is that where the seaside is?’

‘There are lots of seasides, everywhere. You know that – we’ve looked at the globe together.’

‘Yes, but are we at the right seaside?’

‘Not yet, love. We’re going on the boat, and we’ll stay in a hotel tonight, then we’ll set off for the seaside in the morning.’

Her lips quiver. ‘I’m tired. I want to go home.’

‘I know you’re tired, darling. I’m tired, too. But it will be lovely when we get there, won’t it?’

‘Will Daddy be there?’

‘No, I told you, Daddy has to work. This is a holiday for just you and me.’

A holiday leading into a whole new life, I hope. I sigh. I can’t possibly explain this to Olivia, and just hope that my love for her will see us through what’s going to be a traumatic awakening: that her father will no longer be part of our lives. But for now, I have to treat it as a holiday, while I gather my thoughts. Poor Olivia has never known anything except our big house, with her own bedroom filled with everything a loving mother – and her father’s money but not attention – can provide. It’s going to be a culture shock, for sure. But we will find a way through. We have to.

‘I can ring him and let him know we got there safely,’ she states.

‘Okay. When we get to the hotel.’

I don’t argue. It’s a little lie for peace as I pay for two foot passengers on the Leinster to Dublin. We’re directed almost immediately to the embarkation point, where I slump onto a wooden seat, shell-shocked with exhaustion. I’d worked out the timetable weeks ago, so that we’d be here pretty much on time, but with privatisation causing turmoil on the rail network, we’d missed a connection, and I’d almost broken down at that point, wondering why I ever thought I could do it. A British Rail ticket collector, who seemed to know absolutely everything, worked out a different route that would get us here on time, if we were lucky.

In hindsight, I realise how lucky we were.

In the passenger waiting area, I pull Olivia onto my lap and rock her, humming one of the little ditties she’d learned at school. She’s bright-eyed and limp with tiredness. I brush back the fuzz of fair curls sticking to her forehead and whisper, ‘Don’t sleep yet, love. We’re going on the boat now, and there’s a bed on the boat for you.’

‘I don’t want to go on a boat. I want my own bed.’

‘It’s a holiday, love. We always sleep in different beds on holidays.’

‘I don’t want to.’

The whimper is punctuated by a wide yawn, and a few minutes later, thank goodness, the barrier across the foot-passenger gangplank is hauled back, and a man gestures for us to embark. I stand, but Olivia refuses to let go and be put down, clinging to me like a monkey. I’m wondering how on earth I’ll manage to carry her, two cases and a rucksack, when a grizzled old gentleman in a tattered tweed jacket tips his hand to a flat cap and, with a thick Dublin accent, says, ‘Girl, ye looks fair fraught, so ye do. Let an auld one give yous a lift?’

‘I’m so sorry,’ I say, utterly spaced out. ‘Please leave it. It’s too heavy. There’s probably someone else…’

But everyone else is making their way onto the boat, passing by, eyes averted. Even the staff seem to be avoiding the problem. I guess they don’t get paid enough to care. But surely caring is something you do because you want to be kind?

‘Sure, they’re light as a feather,’ he lies, heaving the cases and leading the way. ‘I was over seeing my own family, you know? I’ve got five boys and two girls. Three boys in New York and two in Birmingham, and the girls safe at home with their weans. Seventeen grandchildren I have,’ he gasps proudly, ‘and two on the way.’

‘That’s wonderful,’ I say, not really meaning it. I don’t understand why it’s perceived as an achievement for one man to father a whole tribe when the planet is so overpopulated. But the man is kind and is useful in more ways than one. He knows his way around the ferry and leads us straight to the cabins. Ours is cramped, with a salt-scoured window and two berths.

‘Thank you so much,’ I say to the old man, who is standing, head cocked, as if waiting for my story in return, ‘but I think I’m going to have to lie-down with her.’

‘Not a bother,’ he responds, tipping his cap with two fingers. He backs out and closes the door behind him.

I slump onto the narrow bed with Olivia crooked into my body and hum a lullaby. She’s asleep within minutes. I’m exhausted, too, mentally and physically. It takes me a while to settle, though. I’m almost surprised we got this far without Graham catching up with us. At every step along the way, I imagined him driving behind us, getting closer and closer. Perhaps he’s even on the ferry, in the cabin next to us, watching for an opportunity to steal Olivia back. My breath quickens, and I make myself breathe slowly and evenly. I can’t let my imagination override my determination. I’m not just saving myself; I’m saving my daughter, too.

I’m awakened by a klaxon belling through the tannoy system, warning us we’re about to berth. I must have slept for the full four-hour crossing.

There’s no time for washing, but I make sure Olivia does her teeth, and I brush her hair. She’s subdued, confused and glares at me with impotent accusation, having realised that this is no normal holiday. Graham organises everything with clockwork precision: trains arrive on time, providing first-class accommodation, and we’re chauffeur-driven to hotels where porters carry our bags and there are real beds to sleep in.

I’ll find a hotel for the night, because there’s another hard day of travelling ahead of us. But everything will be fine when we get to the cottage. It’ll be basic, Grandma had warned me. I’ll actually have to draw water from the well! But if several generations of Grandpa’s family managed to survive there, so will we. When I open the cabin door, I’m surprised to see my saviour of a few hours ago, waiting outside.

‘Patrick, at your service, ma’am,’ he says, with a flourish of his cap. ‘Jest thought I’d give yous a hand with the bags.’ He bends to address Olivia. ‘And how’s the pretty colleen? Better for a sleep, no doubt?’

‘I’m not Colleen,’ she states. ‘I’m Olivia Adams, and my father is going to come and get me soon.’

I’m slightly shocked by her statement, which tells the whole story in a sentence. ‘She’s tired,’ I counter. ‘We’re going to stay in my great-grandpa’s cottage, for a holiday.’

I don’t mention that Great-Grandpa won’t be there, and I don’t mention that I’m more than a little worried about how we’ll be received. Though I’m Irish by descent, I don’t sound like it. It bothers me that people can be hated for something they didn’t have any say over, such as their accent, where they were born or who their parents are, but Olivia’s present tone won’t endear us to anyone at all.

He doesn’t seem to take offence, though, and hefts the bags, despite my protest.

As we come out into the fresh air, I instantly feel that I’m in a foreign land. I glance around at the cranes, the warehouses and beyond, on a small rise, the rows of terraced houses and wonder why I feel this way, when the landscape is not so dissimilar to where I grew up, in Birmingham.

‘Have you any idea where we’ll find a taxi?’ I ask.

He indicates with his chin and begins to walk. ‘Where will yous be heading?’

‘A hotel for tonight,’ I said. ‘We need to rest up while I find a way to get down south. We’ve never been to Ireland, so I haven’t a clue.’

‘Good hotel?’ he asks with a crooked grin, probably having seen the Harrods logo on the cases.

‘Not the Ritz,’ I said dryly, ‘but better than a boarding house.’

‘The Gresham then.’

‘Isn’t that expensive?’

‘They have basic rooms, too, and it’s right in the centre. Ideal for yous, I’m after thinking. But look,’ he adds. ‘It’s a few miles into the city. We can give yous a ride. Ye don’t need a taxi.’

He puts the cases down and waves at someone in the distance. A young man, lean and fit, walks up to us, a smile of greeting on his face. He dumps a hand on Patrick’s shoulder, casting a curious glance at myself and Olivia. ‘How’s yerself, Grandpa? All well over the water?’

‘Good, good, good,’ Patrick responds in a machine-gun spatter. ‘This lass and the wean need a lift into the city.’

‘I’m Grace,’ I say, holding out my hand. ‘And my daughter, Olivia.’

He squeezes my hand briefly and gives us a charming smile. ‘Sure, grand. Follow me. The car’s over the way.’ He lifts the bags as though they weigh nothing and heads towards the car. I grab Olivia’s hand and follow, bemused by the ease of this unexpected assistance.

As we walk, the old man provides a running commentary for his grandson on his family in England. They’re all grand, so they are. Doing well. The men have jobs in the steelworks, but there are rumblings of closure; but, sure, won’t God provide? The women are kept busy, sure they are, with the weans clamouring for food like a pack of puppies.

The young man stops at what used to be a Cortina. The word ‘car’ doesn’t describe the remnants of the vehicle. It’s a wreck on wheels, and I’m stunned it’s on the road at all. Its orange paint blends down into rust and peters into holes through which the chassis is visible. The bonnet is tied down with baler twine, and the back windscreen is a spider’s web of cracks, as though it had been hit with a brick. Maybe it had.

I don’t know whether to laugh or refuse the lift, but out of politeness do neither. My cases are stowed in the boot, which is closed with a hefty slam as it doesn’t seat well. My old saviour offers me the front seat, but I reach for the back door. ‘I’d better sit with Olivia.’ She wouldn’t want to sit next to a stranger, kind or otherwise.

I try to open the door, but it’s jammed. The grandson reaches past me and gives it a heave. It opens with a complaining squeal, and he gestures for us to enter, as though it’s a grand carriage, adding, ‘Mind the floor, why don’t ye? It’s a bit ropey.’

He gives the door a mighty slam behind us, making us wince. I grin at Olivia, and thankfully, she grins back. It’s an adventure, after all.

‘Daddy’s got a Rolls-Royce,’ she states as we pull smoothly away, the engine apparently in better condition than the rest of the car.

I want to shrink into the upholstery with embarrassment.

‘Oh, has he, indeed?’ Patrick responds, glancing over his shoulder. I hear the smile in his voice, though I can’t see it.

‘Yes, and it’s silver, like the princess’s dress. Sometimes he goes to work in it, and I go in it, too. But not often, ’cause Mummy drives me to school in the blue Volkswagen because it’s a safe car.’

‘And how old are ye, Olivia?’

He’s remembered her name somehow.

‘Six and three-quarters.’

‘Six and three-quarters is a very fine age, to be sure.’

‘And when I’m seven, I’m going to a big school, after the holidays.’

‘Well, now. That will be exciting, eh? And what are you going to be when you grow up?’

‘I don’t know yet,’ Olivia answers seriously. ‘I like drawing. But maybe I’ll work in Daddy’s firm. Arthur is going to work there, only he doesn’t want to. He wants to be a deep-sea diver.’

Deep-sea diver? Poor Arthur. I suspect that was a wildly inventive wish; anything but become his father’s understudy in the world of commerce.

‘Arthur?’ Patrick queries, looking over his shoulder.

‘My big brother,’ Olivia says.

‘By my husband’s first marriage,’ I feel obliged to inform them. ‘He’s a lot older than Olivia. He’s just finished university.’

‘Ah.’ There’s a wealth of understanding in the word. ‘Did she die, Arthur’s mother?’

‘Yes, but, well, they’d been divorced for a while.’

I belatedly recall that divorce is illegal in Ireland.

The road into Dublin is quiet compared with what I’m used to, and several cars going in the opposite direction seem to be in much the same state as the one we’re in. A couple of tractors, old and tattered, pass in the opposite direction, too, and there’s even a donkey cart which I point out to Olivia, who stares in amazement. She’s seen horses, of course, when Graham took us to the races in Cheltenham, but nothing like this.

We cross a bridge and are suddenly within the city environment, with its tall nineteenth-century buildings and rows of shops. The Gresham Hotel is a huge block of a building with what seems like a thousand windows. We pull in to the kerb, and Patrick’s young driver gets out and heaves my bags from the boot. He insists on carrying them inside for us.

I lean down and thank Patrick for his kindness.

‘Ah, not a bother, not a bother,’ he mutters, as if doing someone a favour is simply part of life.

‘It meant a lot to me,’ I respond, and his dark, wrinkled skin seems to grow a shade darker. I don’t want to embarrass him further, so I leave it there. I try to offer the young man money for the petrol, but he shrugs it aside with a grin. ‘Glad to help. Sure, it wasn’t out of my way at all. Have a good stay in Dublin, won’t ye?’

And here we are, in Ireland.

I don’t feel complacent, but the wide stretch of water between myself and Graham provides hope that the hounds chasing us will have lost the scent.